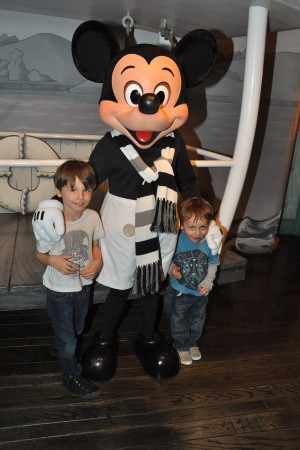

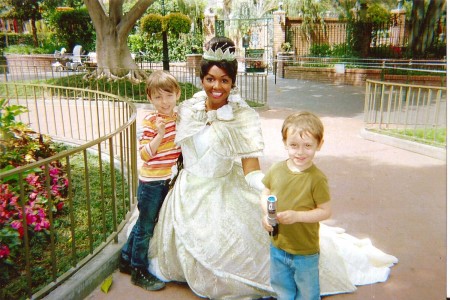

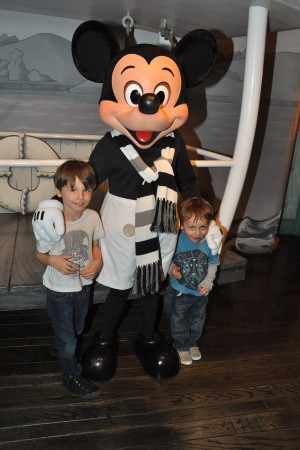

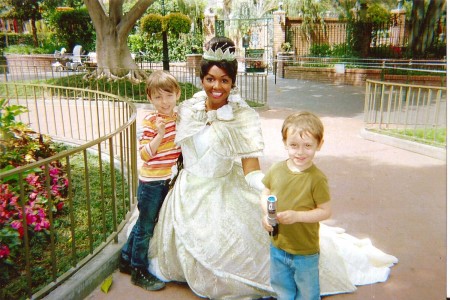

We went to Disneyland! And everyone was super nice to us and we had a great time. We actually went in April, but it’s taken me ages to write about it, mostly because I have a weird fascination with Disneyland that’s hard to explain.

It’s only my second trip to Anaheim, and my third to a Disney theme park. I went to Walt Disney World as a kid, with my mom. When I told her about our vacation plans, Mom said: “What I remember from that trip is that at the end of the day my face hurt, from smiling so much.”

I don’t remember that trip much, but when I went to Disneyland as an adult it was with Sam and my friend Frank Jones, who’s something of a Disneymancer. He has such a deep understanding of the place, its tidal ebbs and flows, that he was able to lead us from ride to ride as the crowds parted around us. Afterwards I told Frank that I was mostly struck by the psychology of the place. It’s obvious that every turn of path, every flower and shrub, has been carefully selected to keep the visitors happy and calm: and I wanted to know how they did that.

Frank pointed me to a couple of books: Designing Disney (A Walt Disney Imagineering Book) and Designing Disney’s Theme Parks: The Architecture of Reassurance

and Designing Disney’s Theme Parks: The Architecture of Reassurance . These are both great! The first is a collection of interviews and reminiscences with some of the “imagineers” who built the park, while the second is a more academic analysis of Disneyland’s place in the cultural zeitgeist.

. These are both great! The first is a collection of interviews and reminiscences with some of the “imagineers” who built the park, while the second is a more academic analysis of Disneyland’s place in the cultural zeitgeist.

Both confirmed what I’d intuitively felt: every aspect of Disneyland—from the placement of physical structures and paths to the selection of colors to the “random” appearance of street performances and signature characters—is engineered to produce a particular response. Disney wants its guests to feel “playful”—excited, yes, but a trusting excitement rather than a nerve-jangly one. Disneyland offers reassurance but it never cedes control.

The parks are designed so that a fresh adventure beckons any way you turn, and no choice is wrong. At the same time, there’s a moralizing element to the landscape: Walt was a railfan, and the Disney theme parks subtly push an anti-car and pro-mass-transit ethos along with a relentless optimism in technology and progress. This futuro-utopianism has, ironically enough, became almost quaint. In modern sci-fi the naïve dreams of the Rocket Age have curdled into punk-anarcho-cynicism: but at Tomorrowland everything is still brightly painted and headed for space.

From Designing Disney’s Theme Parks:

If Disneyland as a whole—its spatial reassurances and human scale, its concern for providing visual pleasure, its walkability and fanatical cleanliness—was a critique of Los Angeles and the modern city, then Tomorrowland was supposed to be the spot where solutions to urban problems were dramatized. A place where Walt could try to articulate a future so compelling that his guests and their children would want to go home and make it all come true, down to the moving sidewalks and the dancing fountains…In the early 1960s, Walt’s inner circle of Imagineers (“imagineering” is surely the ultimate Tomorrowland word, redolent of rocket fuel and derring-do) remember the founder lugging books on city planning around with him and muttering to himself about traffic, noise, and neon signs.

And from the beginning, this can-do utopian spirit grated on the nerves of elite commentators. Then, as today, the worst possible crime among the upper classes is to be found tacky. Much better the evil than the ersatz.

Designing Disney’s Theme Parks quotes a review from the Nation in 1958:

“The overwhelming feeling that one carries away is sadness for the empty lives which accept such tawdry substitutes. On the riverboat, I heard a woman exclaim glowingly to her husband, ‘What imagination they have!’ He nodded, and the pathetic gladness that illuminated his face as a papier-maché [sic] crocodile sank beneath the muddy surface of the ditch was a grim indictment of the way of life for which this feeble sham represented escape and adventure.”

Do you know what I love best in that quote? It’s the [sic]. Because the snobbery and elitism of the passage really doesn’t need to be deconstructed: it’s self-caricature, it’s farce. (How dare Mr. and Mrs. Jones have the effrontery to publicly enjoy a day at a theme park, when they haven’t even the wherewithal to pack up Timmy and Polly for a real Amazon adventure?) But the [sic] is glorious. Because, of course, it really should be the English “paper mache,” as the essay’s in English. But failing that, the proper French is “papier-mâché”: the Nation reached for the more pretentious option and got it wrong. So that [sic] is just like a clean stiletto through the ribs. I love it.

And building on that deconstruction, the book crescendos:

The critic for whom all pop culture is inauthentic and crass, the by-product of grasping capitalism, is probably never going to like Disneyland. And the critic from whom the preoccupations of American mass culture over the past half-century—the TV Westerns of the 1950s, exploring the conflict between institutions and individuals; the Cold War tensions played out in the space race of the 1960s; the battle for the custody of earth’s green spaces; the preservation of the city—elicit only contempt won’t care much that the icons of the Disney parks were located on precisely those sore spots in the national psyche. Nor that these icons embodied, in an engrossing new medium, the themes of a half-century’s worth of thought, debate, and worry. That Disneyland needed to create an architecture of reassurance in the first place meant that the issues raised by the iconography of the park were, at some level, profoundly disquieting.

…

Fantasyland, in particular, was constructed as an environment that synthesized public, postwar ideas about myth, ritual, and psychic redemption. Its architecture fused postwar enthusiasms for imagination, horror, hallucination, and magic with deep-felt desires for safety, security, restraint, and direction.

…

Human beings have always been tempted to envisage a world better than the one they know. The literature on Eden, paradise, or utopia is vast. Besides fictional writers, humanist scholars, and social scientists (including Karl Marx) have tried to envisage life in the good place. Even the greatest minds have failed, however, in one test—important to William James among others—namely, that such a place should stimulate the imagination, that its effect must not dull too soon. Understandably, Walt Disney does not score total success where so many talented people before him have failed. Yet I would like to argue that he has succeeded to an extraordinary degree—that he has introduced elements into his conception of a good and happy place that others have missed.

I don’t think for an instant that Disney should be above criticism. Any company that has such power as theirs, the ability to commodify the myths we tell our children, needs to be loudly and constantly and carefully critiqued. I do think, though, that there’s a kind of reflexive anti-Disney sentiment that’s founded purely on elitism. I would even argue that there’s something subversive about Disneyland and the wordless argument it makes in favor of density, transit, and an ethos of civic planning that puts human psychology at the center.

The thing my mom remembers most about Walt Disney World, after all these years, is that her face hurt from smiling so much. I wonder what my kids will remember?